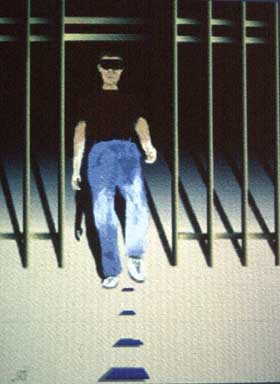

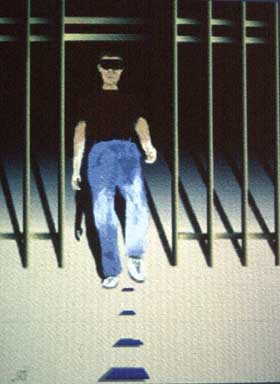

Self-portrait by Tom Riess

AUGMENTED REALITY HELPS PARKINSON'S PATIENTS WALK AGAIN

Self-portrait by Tom Riess

When podiatrist and outdoorsman Tom Riess heard about off-the-shelf "augmented reality" (a kind of virtual reality) glasses you could buy to watch TV while mowing the lawn or playing golf, he knew he had to get a pair. But not because he wanted to play golf. Tom Riess wanted to walk again.

Sixteen years ago, at age 33, Riess was stricken with Parkinson's Disease, a progressive, degenerative neurological disorder that afflicts between half a million and one and a half million Americans alone.

A determined man with a penchant for invention, Riess was not about to let the disease take over his life. A true garage scientist, he worked tirelessly to understand and redress his systems. using his own body as what he calls his "24-hour research laboratory,"

He began by searching for ways to thwart the impaired walking ("akinesia") symptomatic of Parkinson's, thought to result from depletion of the neurotransmitter dopamine in the brain's movement control centers. He discovered that walking up regularly-spaced objects like stairs triggered the well-documented but little-understood "kinesia paradoxa" (paradoxical movement) effect that could return his gait to almost normal. So did shopping in Safeway, where the floors were lined with evenly-spaced black and white tiles.

Apparently, regularly-patterned visual cues in Riess's field of vision set up an "optical flow" that permitted normal movement. Without the flow, Riess was frozen.

"Obsessed" with finding a way to transport and extend the cues, Riess worked night and day in his garage, devising ingenious, Rube Goldberg-like devices. Among his solutions, he attached playing cards to the tips of his tennis shoes with coat hangers; as he walked, the cards presented themselves as evenly-spaced objects in front of him. "I'd bring my cues with me," says Riess. "Not too socially acceptable, but it worked!"

Then he heard about the Virtual Vision Sport Personal Viewing System: "augmented reality" goggles that superimpose a virtual TV screen image onto the real world a few feet ahead of the wearer. "They superimposed imagery onto reality without obliterating reality," explains Riess. "You could see the world, and also affect it by placing cues on the ground in front of you." Maybe, Riess reasoned, this was just what he'd been looking for.

Virtual Vision directed Riess to Suzanne Weghorst, Director of Interface Design at the Human Interface Technology (HIT) Lab (a joint research unit of the Washington Technology Center and the University of Washington), who was working on devising medical applications of the glasses.

When Riess put on the goggles, he saw the real world, "augmented" by a series of small, colored, moving squares, projected infinitely into space at regular intervals in front of him. The virtual squares were bounced from a video feed onto a reflective lens before one eye. Though his other eye was unobstructed, a trick of Riess's brain took the virtual images and superimposed them in front of both eyes.

"The result," explains Weghorst, "gives you a view of the real world with a large-screen TV set embedded in it. It's using VR to augment the world -- to adapt our environment to better fit our needs." Wearing the glasses, Riess could walk almost normally.

Tom Riess testing his glasses at the HIT LabGreatly encouraged, Riess founded a small, self-funded company, HMD Therapeutics in San Anselmo, California, to develop and test his own refined, prototype versions of the glasses. His Central Field Cueing Device Glasses feature an array of LED's (the blinking lights in many electronic devices) and a computer chip embedded in the sidebar of what look like normal, wraparound sunglasses -- "not like some strange cyber-apparatus," quips Riess. The LED's produce thin, virtual bars that scroll down and are projected onto a transparent screen across the wearer's entire field of view. The glasses also contain mercury switches that track head movements and "choreograph" the virtual cues accordingly.

His most recent revision, Virtual Vection Glasses, use LED's to generate peripheral cues. These not only permit normal walking, but also help to suppress "dyskinesia" -- the jerky, uncontrolled movements that can result from the body's attempts to process apparently irrational peripheral movement, as well as from L-Dopa medication build-up.

All of Riess's new glasses meet his exacting requirements: they're light, portable, inexpensive, easy to manufacture, offer hands-free control, and are socially acceptable - even stylish.

Tom Riess presenting at Avatars97Riess recently tested his glasses on members of his Parkinson's Disease support group: "They put on my glasses, and they could walk. Plus their tremors disappeared completely. I was pleased -- but not surprised."

"It is surprising when something new comes from outside the established domains of science," notes Weghorst. "It's true garage science; it's exciting. Augmented reality offers new hope for customized treatment of a wide range of perceptual and movement disabilities."

And in particularly exciting news, Riess and Weghorst have just received an SBIR (Small Business Innovative Research) Grant to help fund their continuing research. Riess has recently licensed his patent to a Southern California-based company which is refining and perfecting his prototypes into a product. The SBIR grant will be used to test this product and ultimately, Riess hopes, to gain FDA approval so that others with Parkinson's can benefit from Riess's amazing work.

"This disease has taken a lot of my life away," says Riess. "The more I can take back -- the more I can reclaim my life -- the bigger the dividend for me and my family."

Photos courtesy Tom Riess

Return to VirtualGalen/VirtualHealing

![]()

Please

send site comments to our

Webmaster.

Please see our notices

about the content of this site and its usage.

(cc) 1996-2003 Galen Brandt, some

rights reserved under this

Creative Commons license.